RelatioNet RA ZI 30 YA PO

Zimra Ravizki

Interviewer:

Tamar Eiger & Eshchar Zychlinski

Email: esh2005@gmail.com

Address: Kfar Saba, Israel

Survivor:

Code: RelatioNet RA ZI 30 YA PO

Family Name: Ravizki First Name: Zimra

Father Name: Fayvish Mother Name: Etka

Birth Date: 12 / 9 / 1930

Town In Holocaust: Wloclawek Country In Holocaust: Poland

Status (Today): Alive

Address Today: Kfar Saba, Israel

Relatives:

Family Name: Kaminski First Name: Yosef

Father Name: Alexander Mother Name: Sarah-Shoshi

Relationship (to Survivor): Husband

Birth Date: 15 / 8 / 1921

Town In Holocaust: * Country In Holocaust: Poland and Russia

Profession (Main) In Holocaust: Soldier

Status (Today): Alive

Address Today: Kfar Saba, Israel

The Jewish population in Wloclawek in 1931 was 10,209 out of a total 55,966. Yiddish and Hebrew culture flourished with libraries, newspapers, a theater, a choir, an amat eur orchestra, and sports clubs. During the II World War about 30% of Wloclawek town has been destroyed.

eur orchestra, and sports clubs. During the II World War about 30% of Wloclawek town has been destroyed.

On September 14, 1939 the German army entered and aided by local sympathizers. A few days after they entered Wloclawek, the Germans burst into a private house where Jews were standing in prayer on the eve of the Day of Atonement, and ordered those present to get out and run. Then they gave the order "Stop," but some of the Jews did not hear this order being given and went on running. Then the Germans opened fire and killed 5 or 6 of them. On the Day of Atonement itself the Germans organized a pogrom and burned down the two large synagogues of the city. The fire also spread to several private homes. The Jews tried to save the burning houses. They also threw their possessions out, in order to save them as well. However, then they were robbed by the Polish mob. These fires were set mostly by the men of the SS. In many cases they turned the synagogues into stables, into factories, into swimming-pools, into places of entertainment, into health centers, into prisons and even into public latrines. At the end of the pogrom, the wounded were buried alive together with the dead.

Afterwards, the Germans took all the Jewish men from one of the buildings, 26 persons, and forced them to sign a declaration that they themselves had set fire to the synagogues and buildings. After the Germans had obtained this declaration they told the men who had been arrested that they would be punished for committing arson and could save themselves only if they paid a ransom of 250,000 zloty. The Jewish population of Wloclawek collected the necessary sum amongst themselves and the men were released.

The Germans began to la unch hunting expeditions into the houses. They caught about 350 Jews and put some of them in barracks and some of them in the Muehsam factory. From there they were taken out to work every day, but given no food. Only their families were permitted to bring them food. After many pleas, those who had been arrested were permitted, after many checks, to visit their homes from time to time in accordance with a special leave of absence permit, in order to wash, change their clothes and eat.

unch hunting expeditions into the houses. They caught about 350 Jews and put some of them in barracks and some of them in the Muehsam factory. From there they were taken out to work every day, but given no food. Only their families were permitted to bring them food. After many pleas, those who had been arrested were permitted, after many checks, to visit their homes from time to time in accordance with a special leave of absence permit, in order to wash, change their clothes and eat.

The regular work of the 350 who had been arrested did not by any means stop the abduction for work of Jews in the streets of the city. Apart from that, there was the Jewish Council (Judenrat), which had been appointed in place of the former Community authorities. It would supply a certain number of Jewish workers every day, in accordance with German demands. Those who had been taken away and those who were abducted for work were beaten and abused unmercifully. One of these Jews, Jacob Heiman, 52 years old and too weak for physical labor, was beaten and stabbed with a dagger while he was working. A few days after when he returned home, he died of his injuries.

In October the Germans decreed that the Jews must attach a yellow badge to their clothes in back, and that they must not step on the sidewalks of the streets, but walk in the middle of the streets. After a short while, the Germans imposed another fine on the Jewish population, of 500,000 zloty, for the imaginary offense of not obeying the ban on using the sidewalk.

The Germans closed and confiscated the factories and stores belonging to Jews. The schools were closed too. The Jews were required to register all their property, and a Jew was not permitted to keep more than 200 zloty in his home. There were many cases of Jews being beaten and tortured. They used to beat them not only during f orced labor and not only when they had some complaint, but also for no reason at all. They would simply go up to Jews passing in the street cry "Zhid" and stop to hit them.

orced labor and not only when they had some complaint, but also for no reason at all. They would simply go up to Jews passing in the street cry "Zhid" and stop to hit them.

At the end of 1939, many Jews were sent to other places, and the remaining Jews were moved into a ghetto in October 1940.

During the first two years of the occupation the German extermination activities were not yet "total". All the above mentioned pogroms, executions, individual or group murders, accounted for the deaths of probably about 100,000 Jews. The Germans realized that the old-fashioned pogroms alone could not "solve the Jewish problem". On 24-27 of April 1942, the ghetto was liquidated when the remaining Jews, mostly the elderly, women and children were sent to their death in the extermination camp Chelmno.

Wloclawek was liberated on January 20, 1945. The first post-war years were marked with rebuilding and development of old factories and workshops, and their modernisation.

Wloclawek was liberated on January 20, 1945. The first post-war years were marked with rebuilding and development of old factories and workshops, and their modernisation.

I was an only child, and a spoiled girl. I used to be with the family all the time.

At home we talked Polish. We were educated with values, family life and honesty. The city was very cultured, with youth movements and courses for the adults. My parents were very active and sang in the choir. My father was not a Zionist, but he loved Hebrew literature and Yiddish. He was the manager of a factory, and the whole family lived in an apartment which was located above the factory. My memories from that time are the best. I went to a private Hebrew school where we learned Bible and Hebrew classes. When I grew up, I also went to Yiddish classes in the afternoon. I and my mother often walked to my grandmother through the main street, where we met a lot of acquaintances. We were used to stop at a bakery and eat cheese cake with a slice of watermelon.

I was not aware of the Anti-Semitism and even had two non-Jewish friends, with who's I played. They were the daughters of the guard at the factory my father managed.

In February of 1943, when my father sent me to the Aryan side, he firstly searched me for any Jewish characteristics and made sure that I didn’t take anything with me. He didn’t know that for all of the war years, I had a picture of me with my parents. On September 14th, the Germans took over Wloclawek with no battle. People didn’t know if they should stay and be subordinate to the German government, or if they should flee to Russia. My father and my uncle also planned to run away, and had already bought a cart, but my mother said that she would not go without my grandmother, who was too old, so all of the family stayed in Poland.

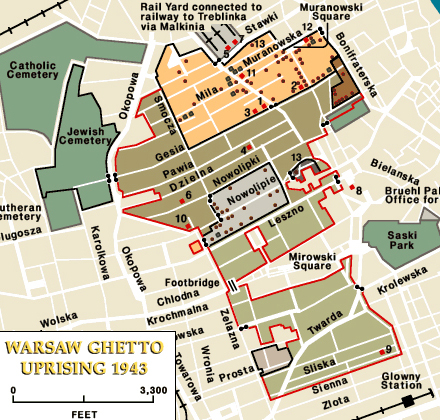

My father made connections in Warsaw, and went there to rent a room. My mother and I joined him in December, before Christmas. We took the train to Warsaw, hiding our Jewish identity. In 1941, the Germans sealed all of the ghetto exits. The ghetto was for the Jews who lived in the poorest areas of Warsaw. The Jews from the richer areas had to exchange their fancy villas for

When the people who lived around Warsaw came to the ghetto, there weren't enough dwelling places. There were lots of illnesses and many people died in the streets. It became a normal view.

The first Akzys (roundup of Jews from conquered territory for transport to death camps) to the extermination camp - Treblinka were in 1942. One day, me and my parents went in the ghetto, and saw an advertisement which had be written on that the Germans asked for voluntaries who agreed to go to another city, where they could work. Some people volunteered themselves, because they didn't know what was really going to happen. Were some rumors in the ghetto about the gas chambers but no one believed him.

The Germans assembled the Jews in the ghetto according to their professions. We belonged to the community people. The community people were assembled in the community building. In war time, the community building was very derelict. All of the community people were assembled in the building and their families stayed outside the building. Inside and outside the building people shouted one to another. My father was inside. Suddenly, a stranger came to me and my mother and told us that he would take us to a hiding place. He took us to a big basement and there we waited. After a while, this man came back with a pink note called "life number". He told us that these notes were given to the community people who weren't supposed to be sent. He said that he brought that note to me, because it belonged to his two year old daughter who he would hide in the bag on his back. My mother quickly sent me with that man and I cried until I found my father.

At that time, the community people had prepared a little basement where they could hide in advance. It was prepared so they could get out with "life numbers" the next morning and would be sent back to the

Ghetto with the expedition.

Ghetto with the expedition.However, the people who were in the basements were caught by the Jewish police who heard them downstairs. My mother was with these people in the basement. The day after, when the expedition from the ghetto, between them – my father, came over to return the people in the basements to the ghetto, they didn't find them.

My father inquired and found out that my mother was in a hiding place at the Umschlagplatz and tried to find a way to save her. Six days after, me and my father got a note from my mother who wrote: "I am lost, but what about you?" We began to weep and it was the last time we heard from her.

More Jews were sent to Death Camps, so there was again more room in the ghetto and the Germans reduced the size of the ghetto. On January 18th, 1943 the Akzys started again. This time, the people were ready for them, therefore they hid. No one followed the orders of the Jewish Police anymore. When the Germans saw that no one was coming, they stopped the Akzys.

My father convinced me with great difficult to leave for the Aryan side. In order for me to get out to the Aryan side, we had to give a photo to the underground organization, who would determine if I didn't look like a Jew. I passed the "test", and they decided on a date on which I would leave of the ghetto. I and my father went with the group of workers to the Aryan side. The workers went to work, and me and my father stayed hiding in a shed during the rest of the day.

I began calling him by his name, and he interrupted me. He said that from now on his name would be Zigmond, and the woman said that my name was not Zimra anymore. From this moment I would be called Zosha. The separation from my father was very quick and odd. I and the woman separated from Zigmond, and went to the woman's house – the Anna Vonclocska's and Marisha Svitzka's house which was my new residence. Also Halina lived there, Anna's and Marisha's niece. We were like sisters.

I used to talk with my father on the phone from the store downstairs. I called him "Mr. Felix" and he called me "Mrs. Zosha". The conversations had to be very happy and we couldn't show any sadness or grief, for it would look suspicious to the Non-Jew society, who was checking everything around it.

Anna and Marisha cooperated with the Jewish and Polish underground organizations. In order for the neighbors not to tell anything to the Germans, Anna and Marisa warned them that if they talked, the underground organization would kill them.

One day, I was alone at the house, so I sewed a dress for Marisa as a surprise. Suddenly, I heard steps coming up the stairs, and talking in German. Two German officers and two Ukrainian who were collaborating with the Germans, burst into the house holding Halina's brother, Stefan. He was covered with blood. The German officers tried to talk to me, but I was so scared that all I could do is shake and babble. The two officers looked at me and said one to each other that I must be stupid and probably don't know anything. Stefan asked me to move his hair aside for he was tied up. I guess he wanted to tell me something, but when I reached over to him, the officers hit me and Stefan. I was the last person who saw Stefan alive.

When the rebellion of Warsaw was over and the ghetto was on fire, people stood on the stairs of the building and laughed. They said "Fleas are burning". When I passed by them I had to laugh too. But when I got to the apartment, I cried so hard that Marisha had to cover my face with a pillow, so the neighbors wouldn't hear me.

After the Germans had taken control over the area, they decided to punish the Polish for their rebellion. They t

old the people to leave the buildings, and killed the residents of one building. The next building after it they send with other German soldiers. They repeated this procedure with all the buildings in the street. According to my count, the residents of our building were designated to be murdered, but inexplicably we were sent with the Germans as well.>

old the people to leave the buildings, and killed the residents of one building. The next building after it they send with other German soldiers. They repeated this procedure with all the buildings in the street. According to my count, the residents of our building were designated to be murdered, but inexplicably we were sent with the Germans as well.>First, we were led to a church where we spent one night. Afterwards, we arrived at a small town. There the Germans made a selection which separated the young, who were to work camp in Germany, from the older people, who were sent to towns all around Warsaw. The purpose of the selection was to clear up Warsaw's population. In the selection, they wanted to send me and Halina to a work camp and Anna to a town. Anna told the German soldier she would go only with her daughters, me and Halina, and he agreed to send her with us to the work camp. Anna told me that she gave my father her word to stay with me and keep me safe.

In Germany, Halina and I worked at a factory called "Trebin" which created we

apons parts. Halina and I worked in shifts, so that on our free time, we could help Anna who worked as an office cleaner.

apons parts. Halina and I worked in shifts, so that on our free time, we could help Anna who worked as an office cleaner.Leading up to the end of the war, when the Russians and the Americans bombarded Berlin, we were forbidden to work at the time of the bombardments, and had to go down to the shelters. Therefore, at that time I and Halina went to our shed to get more hours of sleep.

The war was over, and we went back to Poland by foot with a group of people. When we got Warsaw, it was destroyed completely.

I wanted to stay with them a little more, because I wanted to get education, and it was very easy to get a matriculation at that time. However, the people who got me out of the ghetto believed it was not a good idea and said I must leave Anna and Marisha. I believe they may have been right.

I never thought of staying in Poland forever, as I had strong roots which didn't make it possible for me to keep my Polish identity. My parents raised the banner of truth and honesty. They taught me to always remember who I am, and I think that is what kept me alive and eventually motivated me to leave Poland, the Aryan side.

1 comment:

Tamar & Eshchar

The translation to many languages is a great idea.

Zvika Schwartzman

Kfar Sava

Post a Comment